On 24 January 2020, the first COVID-19 case in Europe was confirmed in Bordeaux, France. In 6 months, 2.3 million European citizens have contracted the infection and more than 180,000 died from it. More than one third of the world’s population stayed in some form of lockdown for several months, after the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the COVID-19 as a pandemic on 12 March.

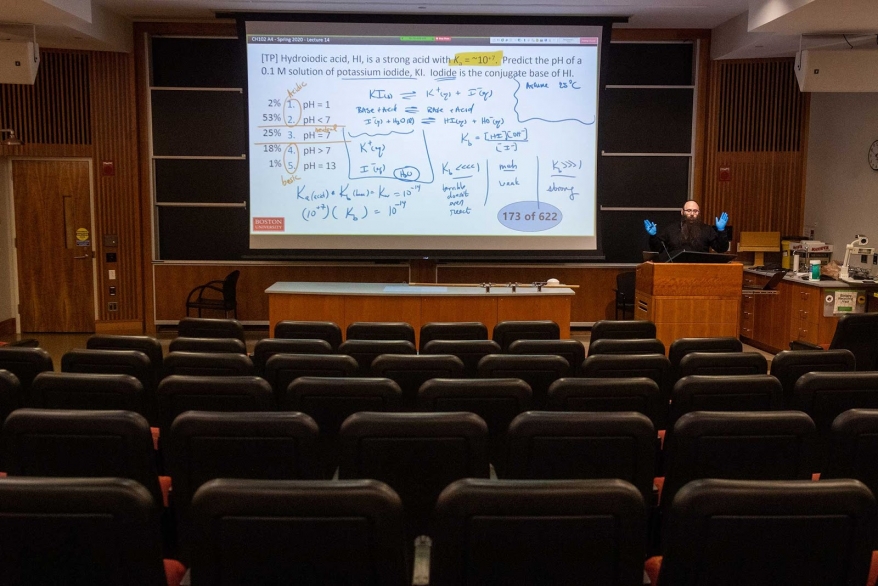

With the exception of research labs working on COVID-19, all research institutions in the EU were generally under lockdown. The vast majority of researchers were required to work from home, whilst universities and research institutes switched to online courses and exams. While the scenario in higher education is rapidly evolving, the impact of the pandemic on the life and work of Early Career Researchers (ECRs) is yet to be quantified.

In the past weeks Eurodoc, the European Council of Doctoral Candidates and Junior Researchers, has collected the contributions of its members, 28 National Associations representing ECRs in Europe, and identified 10 major concerns reflective of the many issues they are struggling with.

Barriers in doctoral training

In the EU, doctoral candidates have to comply with a set of requirements to complete their doctorate and defend their theses. In this exceptional time, some requirements have transformed doctoral training into an obstacle course.

For example, doctoral candidates are sometimes required to complete a visiting period in another research institution or private lab, representing geographical or intersectoral mobility (e.g. EU-H2020-MSCA-ITN-European Training Networks). This was impossible during lockdown, and many doctoral candidates must reschedule or revise their research plans - an operation that is especially difficult for people near the end of their training.

Even when all requirements are met, defending the thesis may not be easy: some institutions and programs require an international committee to approve the thesis, and bureaucracy may complicate moving the final examination online.

Doctoral candidate’s supervision: between neglect and added pressure

In the switch towards remote working and online teaching, higher education institutions are focused on students and researchers holding permanent contracts, with doctoral candidates being sometimes left behind. Many remote-working doctoral candidates highlighted a lack of interaction with supervisors and mentors, with obvious effects on their work. Others, including postdocs, feel an increased pressure from supervisors to produce results and publish, in the wake of possible funding cuts and grim career prospects. Moreover, there is a widespread concern for a lack of training for supervisors to adapt to the post-pandemic situation.

Problematic access to research resources

The switch of higher education and research institutions to remote working is not yet complete, and several problems remain to be solved, such as access to essential research resources.

Many institutions quickly enabled remote working through technical and administrative solutions, but some resources remain difficult or impossible to access remotely. For example, there is a widespread concern among ECRs about research activities which require access to non-digital libraries and lab physical resources, blocked for months and restarting now under very different rules. ECRs working in groups or at precise physical locations (e.g. archeological or geological sites) may have to stop their work until proper health protocols are in place for their activities. Moreover, ECRs working on data coming from field observations or interviews were severely impacted by the social distancing measures.

Regulations for accessing research facilities are not yet clear and therefore there is a widespread lack of health and security training for ECRs and research staff. Moreover, there is no European framework to make EU research institutions’ regulations uniform, to determine how and when researchers can safely move across Europe. Finally, insurances and social benefits may not guarantee cover for COVID-19-related issues (e.g. health conditions, unemployment, etc).

Lack of an adequate working environment

While the majority of ECRs share positive feelings about remote working, not all managed to switch smoothly to this new reality. Most ECRs stress that working from home does not guarantee the same productivity of office work: spaces are frequently shared with other family members or are inadequate for work, and some ECRs must divide their time between work and caring activities dedicated to children, elders and relatives with health conditions.

Overworking in research was a common problem before the pandemic; unfortunately remote working does not help solve this issue. On the contrary, ECRs complain about increasingly blurred borders between working and private time. Lack of interaction and collaboration with colleagues is also a concern for remote-working ECRs.

Lower productivity and increased precarity

From the ECRs’ point of view, the COVID-19 crisis may amplify and accelerate the workforce casualization process in universities and research institutions. Combined with funding cuts, this may lead to redundancies and will especially affect researchers with short-term and precarious contracts, who are most vulnerable. ECRs were already hit by hiring freezes triggered by the pandemic in the US and UK.

For many researchers, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a decrease of productivity; for some of them, research came to a complete stop for several months. EU institutions, universities and research institutes acknowledge the problem, and provide the possibility for contract and project extensions. However, several funding bodies are not funding extensions, and ECRs are left with the only choice of working unpaid to finish their research.

Unclear future for EU research funding

While the EU is set to increase research and innovation funding following the COVID-19 pandemic, figures continue to fall short of European Parliament requests and of the ambitions expressed by many EU institutions. Moreover, an increase at the EU level will probably not balance the anticipated funding cut that some EU nations are preparing on their research and innovation budget.

Post-pandemic research project funding is a source of concern for ECRs, for both projects started before the pandemic and for future projects. In the first case, there might be issues with funds reallocation where the money was not spent or is now not spendable according to pre-agreed conditions (e.g. consumables, travel grants, research visits abroad, courses, congresses). In the future, different post-COVID-19 R&D budget investments may increase funding inequalities among different European countries.

Budget cuts may heavily impact ECRs, hindering contract extensions, increasing the ratio of short-term, part-time and partially-funded research contracts, and even increase self-funded or unpaid positions.

Negative impact on career development opportunities

The lockdown impact on research is not yet fully quantified, and some research outputs may have been lost, wasted or simply expired following the halt to research projects. This negative impact on research activities and publications could jeopardize the career progression of several ECRs, and hinder progress of doctoral candidates.

A decrease in productivity might generate a gap among different generations of researchers and within the same generation. Many conferences were cancelled, and this has deprived ECRs of valuable networking opportunities, while online meetings have changed the dissemination of ECRs’ work and research collaborations, with impacts yet to be understood. Funding cuts and restrictions on travel had a notable impact on national and international recruitment: universities in Ireland and the UK have halted researchers recruitment, with student enrollment projected to fall in the autumn. EU universities in other countries may follow suit.

Increased sense of isolation and anxiety

The lockdown has had a serious impact on ECRs mental health. Remote working has increased researchers’ sense of isolation and this discomfort contributed, with other factors, to reduced productivity. High levels of anxiety related to fear of infection, possible lay-offs in research institutions and fewer career opportunities contribute to psychological turmoil.

Halt on mobility

The lockdown has interrupted or stopped most research visiting periods abroad (geographical mobility), and work periods in sectors different from academia (intersectoral mobility). These activities can often be a mandatory requirement for PhD defense, or required for awarding research positions or funding. It is not yet clear when it will be possible to resume research mobility and under which conditions.

Increased inequalities

All the issues listed above impact some subgroups of ECRs more than others. Remote working seems to have impacted more on female researchers, reducing their productivity more than males’. ECRs with disabilities, in addition, complained of discriminatory environments due to lack of disability-friendly infrastructure for remote working, while coping with increased anxiety for their health. In the near future, personal or relatives’ health conditions are going to prevent certain researchers to physically return to work, increasing once again the risk of discrimination in hiring and funding.

A European post-pandemic plan for early-career researchers

All the issues presented in this document are common to most of the countries of the European Union, are strictly intertwined, and need to be addressed together. We hope that European institutions will be up to the challenge, and we call on them to elaborate a post-pandemic plan for early career researchers in Europe.

The future of European early career researchers is the future of European research: we cannot afford to lose a generation of them. New challenges are ahead, and we need to be equipped to confront and overcome them.