This article is based on a speech delivered by Oleksandr Berezko, President of Eurodoc, at the Annual Meeting of the European University Association Council for Doctoral Education held at The University of Manchester on June 23, 2022.

What does it mean to do a doctorate in Ukraine now? I will try to provide insights on time and timing in doctoral education under the current circumstances. The following insights were mainly provided by RMU, the Young Scientists Council at the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, which has been a member of Eurodoc since 2014.

Ukraine now

First of all, it is important to stress that the current war did not start in February 2022 but eight years ago when Russia annexed Crimea and seized territory in the East of Ukraine back in 2014. It was the moment when the concept of “displaced higher education institutions” emerged in Ukraine: since the beginning of hostilities in the Donbas region, 18 higher education institutions have been moved from the temporarily ceased territories. The displaced universities managed to resume the educational process and research. However, even last year, most were still struggling with infrastructure, funding, and human resources (this is evident to Eurodoc as a partner in the Erasmus+ OPTIMA project targeting those HEIs). In other words, the Ukrainian education system already had some experience dealing with the results of Russia’s aggression before 2022. Still, the 24th of February brought the situation to a completely different level.

According to the United Nations, at least 12 million people have fled their homes since Russia's invasion of Ukraine, including more than five million who have left Ukraine, and more than seven million, who became internally displaced. These figures may be vastly underestimated, as according to the same source, the number of border crossings from Ukraine since 24 February 2022 is almost 8.8 million. If we extrapolate these data to Ukrainian scientists, it turns out that at least every 4th of them was forced to seek refuge in a safer place. In addition, according to official information released on June 13 by the Minister of Education and Science of Ukraine, 43 Ukrainian higher education institutions suffered from shelling, with five completely destroyed.

This situation was further aggravated by economic problems, martial law restrictions, and general uncertainty. The planning horizon of many members of Ukrainian academia has recently shrunken from several years to several days and even hours. The consequences of war on the mental health of Ukrainian researchers are also worrying and will likely have a long-term impact on their well-being and professional efficiency. Furthermore, it is important to stress that Ukraine has no safe place as Russian missile attacks threaten the whole territory.

So, what does it mean to do a doctorate in Ukraine now? Perhaps the best way to answer this question is to give the floor to some of the current doctoral candidates. Since the situation differs between the various regions, I interviewed doctoral candidates from Kharkiv (the very frontline), Odesa (close to it), and Lviv (far from the current battlefields). I hope their stories will help inform your understanding of the situation.

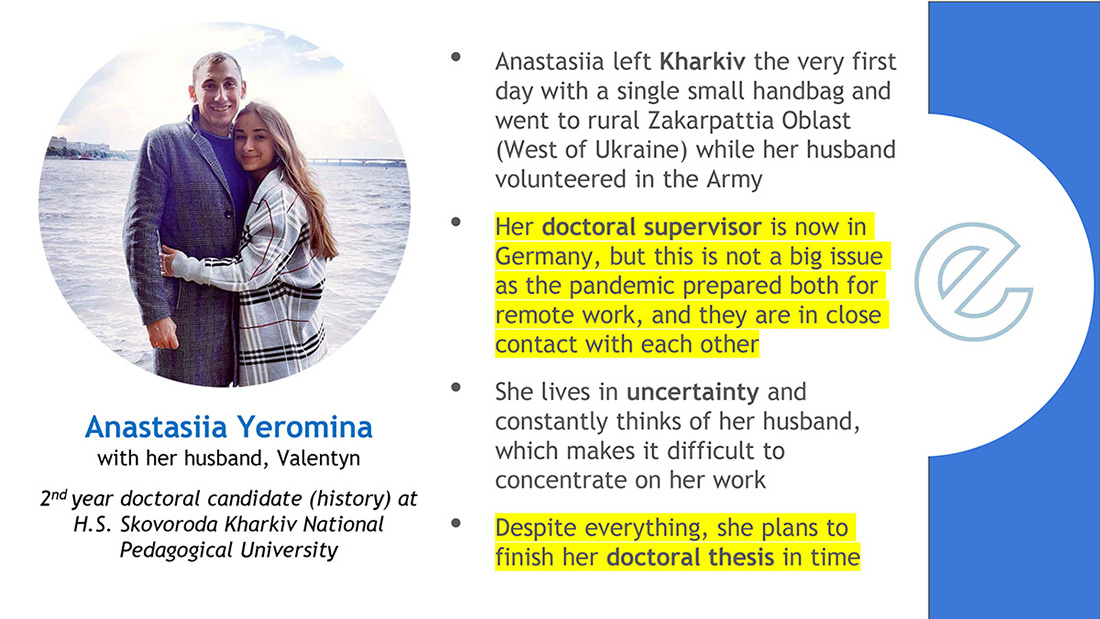

Kharkiv – the actual battlefield

Anastasiia Yeromina, a second-year doctoral candidate at Skovoroda Kharkiv National Pedagogical University, was directly threatened from the very first minutes of the war. The young historian fled Kharkiv 5 minutes after the first explosions. The only thing she could take was a small bag with documents, everything else had to be left behind. Anastasiia currently continues her doctoral studies as an internally displaced person in a rural area in the West of Ukraine, while her husband, Valentyn – also a doctoral candidate at the same university – volunteers in the army. She says that she constantly thinks of her husband and she lives in complete uncertainty, which makes it difficult to focus on her work.

On a more positive note, the pandemic prepared her for working remotely, and she is in close contact with her doctoral supervisor, a Ukrainian refugee in Germany. Despite everything, she plans to finish her doctoral thesis in time.

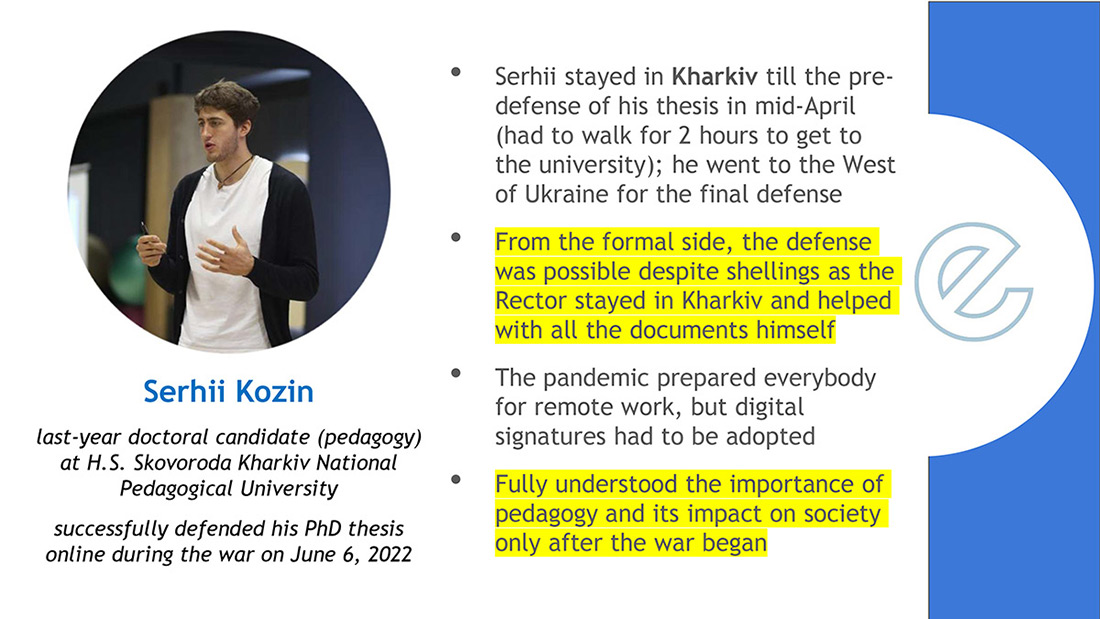

Serhii Kozin, a final year doctoral candidate at the same university, had a challenging experience defending his doctoral thesis during the war. Serhii stayed in Kharkiv until his pre-defense in mid-April, and it was only after this that he went to a safer location in the West of Ukraine to prepare for his final defense.

Preparing for thesis defense in Ukraine requires a lot of paperwork and collecting signatures. Serhii was spending several hours a day getting to the university by foot to complete everything. He is grateful for the support provided by the Rector of the university, who has been staying in Kharkiv the entire time. In fact, the Rector himself covered the windows of the university buildings with duct tape to protect them from shellings.

The war has led to the adoption of digital signatures at the university, which will make the paperwork in the future much easier.

Serhii says that he understood the true importance of pedagogy and its impact on society only after the war began. According to him, good pedagogy can prevent war and genocide.

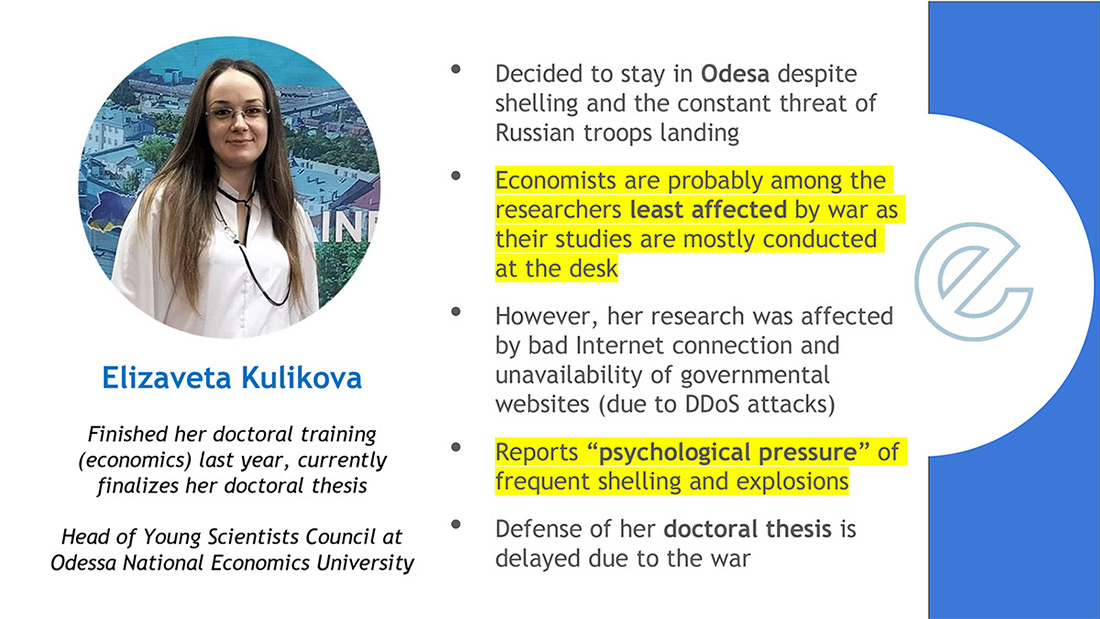

Odesa – close to the frontline

Elizaveta Kulikova has recently finished her doctoral training in economics and is currently finalising her thesis. She is also the Head of the Young Scientists Council at Odessa National Economics University.

She decided to stay in Odesa despite shelling and the constant threat of Russian troops landing. She says that economists are probably among the researchers least affected by war as their studies are mostly conducted at the desk. However, her research was affected by bad internet connection as a result of the war and the unavailability of government websites due to distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks.

Elizaveta reports constant “psychological pressure” resulting from the frequent shelling and explosions, making it challenging to be effective. Furthermore, the defense of her doctoral thesis has been delayed because of the war.

Lviv – a relatively safe city

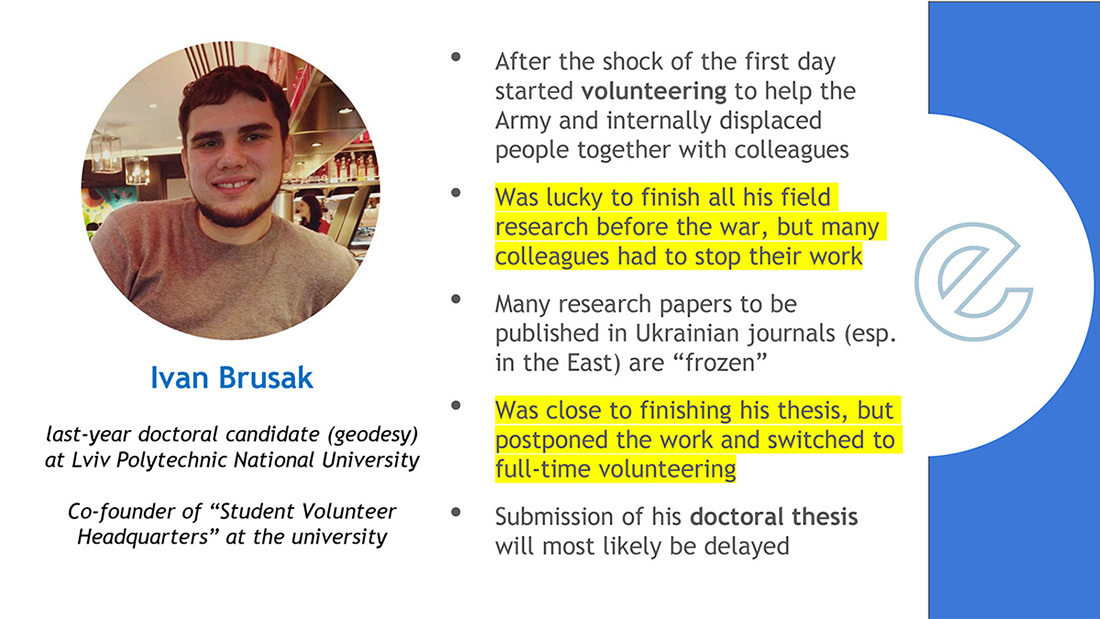

Ivan Brusak, a final-year doctoral candidate at Lviv Polytechnic National University, started volunteering to help the army and internally displaced persons immediately after the war had begun. Together with colleagues, he founded a “Student Volunteer Headquarters” at the university, which became a centre of support for people in need.

Ivan is a geodesist who was lucky to finish all his field research before the war. Carrying out the fieldwork now would have been impossible for him and many of his colleagues.

He says he needs “one more week” to finalise his thesis but cannot find time and focus as he switched to full-time volunteering. Ivan feels that his primary role during the war is helping people.

Submission of his doctoral thesis will most likely be delayed.

A call for partnerships

All the stories of the Ukrainian early-career researchers are of course different, but all of them hope for victory, and most of them cannot wait to continue their work in a peaceful Ukraine.

My colleagues outside Ukraine often ask me how they can help the Ukrainian higher education system and the researchers in Ukraine. As few Ukrainian researchers ultimately want to relocate abroad, various short-term offers are key. These can include invitations to conduct research in your laboratories, temporary work opportunities and remote scholarships. Furthermore, many Ukrainian researchers only had access to paywalled scholarly databases through their university networks, which for many, is currently no longer possible. Accordingly, helping with this access is also a good option.

Most certainly, supporting and practising Open Access publishing is even better because the needed papers would have been available online regardless of the circumstances. So, the war in Ukraine emphasised the importance of Open Science once again.

Maybe most important of all, universities in Ukraine, especially those that have been most damaged, require partner institutions to help them rebuild. So please consider partnering with a Ukrainian university, or, as an individual, lobby your research institution to become a partner.

Oleksandr Berezko thanks Olesia Vashchuk and Hannah Schoch for their help in preparing the article.