The Open Access Week is a yearly event which raises awareness and promotes the free, immediate, and online access to scientific research through Open Access (OA) publishing. For Open Access Week 2018, running from 22-28 October 2018, Eurodoc will publish an article each day on various aspects of OA from international experts.

In this third article of the series, Ignasi Labastida i Juan, Head of Office at the University of Barcelona, explains copyright licences for authors on how their works can be reused.

Many of us have seen a Creative Commons licence attached to a published article, to an item on a repository, or even with a research dataset. But, do we understand the meaning of such a licence? These licences are commonly used but there are still many misunderstandings and misuses that we will try to overcome in this article.

Creative Commons is a non-profit organisation created in 2001 whose main project is a set of open content licences that have become a de facto standard for sharing content. Besides the six main licences that we will primarily address, there are two other tools, CC0 and the Public Domain Mark, that we will cover at the end of our text.

It is important to note that currently, the absence of any legal copyright notice on a work must be understood as an ‘all rights reserved’ situation, and therefore we must first seek permission to reuse such unmarked work. This is the reason why, among other motivations, the licences were created: to explicitly state the type of copyright on a work.

The main requirement for using the licences is that you must hold the copyright on the work you want to share. For instance, although you might be the author of a paper, you cannot attach a licence if you have transferred your copyright or if you have signed an exclusive licence for publication. In many cases, publishers will allow you to post a copy of your paper in a repository, but you must keep the original copyright notice, usually in an ‘all rights reserved’ regime. Nevertheless, there are publishers who allow the use of licences for an author manuscript, such as Elsevier or the Institute of Physics. But those publishers are still the copyright holders, meaning that if anyone wants to use the work beyond what the licence grants, they must first seek permission by asking the publishers and not the authors.

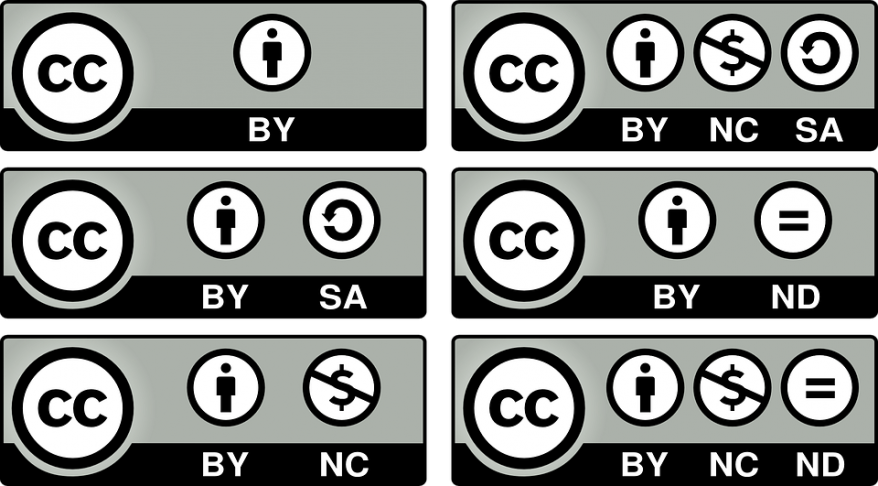

If you are still the copyright holder of your work, you must understand the differences among the licences. Any of the six licences grants users the right to make copies of the work and redistribute it in any medium or format if the use is not for commercial purposes. Moreover, all of them require the user to attribute the work to the author. Beyond these common conditions, there are differences among the six licences. Three of them (CC BY, CC BY-SA, CC BY-ND) allow commercial uses, meaning that anyone can use the work and make a profit without asking for permission, something that is required in the other three licences (CC BY-NC, CC BY-NC-SA, CC BY-NC-ND). Moreover, four of them allow the creation of derivative works and, among them, two require that those newly created works keep the same licence (CC BY-SA, CC BY-NC-SA). This requirement is known as the ‘copyleft’ method which was created by the free software community.

Among Open Access publications, CC BY is the most used licence because it is the one that fulfils the requirements of the definition of an ‘Open Access Contribution’ included in the Berlin Declaration. However, some publishers allow authors to use other licences restricting commercial uses or derivative works. What is important to note here is knowing who keeps the copyright because in many of these cases, and especially when publishing in a ‘hybrid model’, publishers require the transfer of rights. In this case, it is the publishers and not the authors who will authorise further reuses beyond what the licence grants. My advice for authors is to always keep copyright and try to use the most open licence, preferably CC BY.

Creative Commons has always been concerned about the Public Domain and that is the reason why it has always been providing tools for dedicated works to the public domain or to identify works whose copyright term has expired. Currently, there are two tools for this purpose. The first one is the Public Domain Mark, a tool to identify a work in the public domain and especially addressed to galleries, libraries, archives, and museums which might have such works among their collections. The second tool is the CC0, a legal tool that works first as a waiver, secondly as a licence, and lastly for affirming that the author will not exercise any remaining rights on the work. Therefore, if you are the copyright owner of a work, and you want to dedicate it to the public domain, you must use CC0 and not the Public Domain Mark. Among researchers, CC0 is used mainly for datasets because you can waive existing rights on databases granted by European copyright laws, which can complicate the reuse of the data. In general, those rights do not exist in other continents. Although there is no requirement of attribution when using a CC0, I would advise to follow the norms of the scientific community and to give proper attribution of the source when reusing data.

I hope that this short article will help to improve the use of the Creative Commons licences and the understanding of their meaning. Happy Open Access Week!

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License.